Film Arts in Thailand – a research

text and pictures by Joachim Polzer

March 2015

This text is the outcome and product of a six months’ research effort in early 2015 on the position and perspective of independent cinema in Thailand related to World Cinema, – of these –, four weeks were conducted as field research on location in Thailand in January and February of 2015. About 25 people related to Thailand’s indy film scene have been contacted and met for interviews and talks in person.

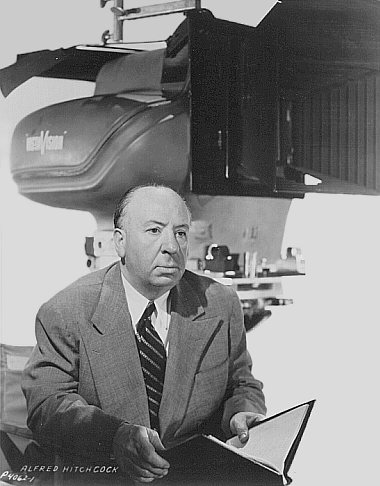

photo above © CMU / Fine Arts / Media Arts and Design MAD

Link: http://www.finearts.cmu.ac.th/mediaartsdesign2/en/2015/02/23/dr-joachim-polzer/

1. The rise of Thailand’s independent filmmaking to its preeminent position in World Cinema

Film scholar Tilman Baumgärtel from Royal University Phnom Penh made it very clear right at the beginning of his book anthology on “Southeast Asian Independent Filmmaking” from 2012: When Apichatpong Weerasethakul won the Palme d’Or at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival – one of the most prestigous awards the international film world has to offer – for his work ‘Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives’, he was not only the first Thai filmmaker to do so, but independently, internationally co-produced film making from Thailand was put now – widely recognizable all over the world – to a preeminent position in World Cinema.

This was not by accident: In 2010 it has been Apichatpong’s third installation to receive a prestigious award at Cannes Film Festival. In 2002 Apichatpong received the Un Certain Regard Prize for ‘Blissfully Yours’; two years later his work ‘Tropical Malady’ won the Jury Prize in main competition at Cannes, the first Thai film to win a prize at any of the “A class Festivals”.

The steep rise to international acclaim was not only wild but tremendous and spectacular from a country that was unknown in arthouse circles before and considered a terra icognita on the maps of international cinema.

Things started to change in 1997, when three directors of television commercials from Bangkok — Nonzee Nimibutr, Pen-Ek Ratanaruang and Wisit Sasanatieng — were considering that film production in Thailand needed to be more artistic and audacious to continue to attract investors and audiences. The framework of a national film industry – still focused on commercial productions with a high-percentage output in genre movies and made only by big studios – needed to be changed, as well as the focus of low-budget film producers who appealed to the local markets only.

It was in 1997, when Pen-Ek’s crime comedy, ‘Fun Bar Karaoke’, was selected to play at BERLINALE, the Berlin International Film Festival – the very first time after so long that Thai cinema had had any kind of an international presence.

2. Thai New Wave Cinema:

“Where are all those filmmakers coming from?”

But it’s no longer only the now “fab four”:

Apichatpong, Nonzee, Pan-Ek and Wisit.

Currently, Thailand’s indy film scene consists of a lively biotope with a huge amount of talents, most of them born during the 1970s, also beneficiaries from the founding, further development and enhancement of several universities and acamenic institutions across Thailand since the 1960s.

Most of those young film making talents graduated from Mass Communication faculties or related departments in Humanities (e.g. Education, Psychology etc.).

While Thailand is missing a national and state funded film school, those Mass Comm Departments are offering an initial understanding and basic training in moving images production, some in dedicated specialilty departments. The two outmost prestigious institutions for film education in Thailand are private-run Bangkok University’s Film Department and Tammasat University near Bangkok.

While domestic film funding und subsidies are still somehow limited within Thailand, the missing bridge from academic training to the practice of artistic film making was often built or enabled by international co-operation and by foreign institutions.

Very helpful in this case proved to be the “Hubert Baals Fund” as a side institution of the “International Film Festival Rotterdam” (IFFR) in The Nederlands. The Hubert Baals Fund, which recently celebrated its 25th anniversary, had been very successful so far in the early tracking of talents, sustaining a co-funding cooperation over a period of several projects (in most cases shorts at the beginning of a filmmaker’s career), while at the same time guaranteeing an international visibility, presence and approval via the IFFR after completion of a subsidized work. And once those early spotted film-makers made their first feature production after time, IFFR often received a first look option or a first offer to present new works at the international festival circuit, even if those long format films didn’t receive anymore subsidies from the Hubert Baals Fund.

Otherwise, some filmmakers also made it to “BERLINALE Talent Campus” for their first time of experiencing international cinema grounds; some went to “idfa” Amsterstam and its market and exchange possibilities. However, Rotterdam remained as an important launch pad for the uprise of the Thai New Wave Cinema.

3. Thai New Wave Cinema:

“Full sprectrum talents in narrative film making”

Even if their newest works may not be any longer attached to the Hubert Baals Fund, it may be fair to mention at least some of those Thai filmmakers, who got their early start and early get going in film production from this particular kind of international cooperation, also in attachment with the International Film Festival Rotterdam:

Aditya Assarat — ‘Hi-So’ (2011); ‘Wonderful Town’ (2006)

Anocha Suwichakornpong — ‘By The Time It Gets Dark’ (2015); ‘Mundane History’ (2009)

Jakrawal Nilthamrong — ‘Vanishing Point’ (2015); ’Unreal Forest’ (2010)

Pimpaka Towira — ‘The Truth Be Told’ (2007); ‘One Night Husband’ (2003)

Uruphong Raksasad — ’The Songs of Rice’ (2014); ‘Agrarian Utopia’ (2009); ‘Stories from the North’ (2005) [trilogy]

Wichanon Somumjarn — ‘In April the Following Year, There Was A Fire’ (2012)

Krisda Tipchaimeta made it with her documentary ‘Somboon’ 2014 to “idfa” Amsterdam, the outmost prestigous international film festival and marketplace dedicated to documentary films.

Anusorn Soisa-Ngim worked on documentaries in gay contexts and AIDS prevention.

A list of talents of the Thai New Wave cinema would be incomplete if not to mention Thunska Pansittivorakul with some of his works: ‘The Terrorists’ (2011); ‘Reincarnate’ (2010); ‘This Area is under Quarantine’ (2008); ‘Happy Berry’ (2004)‘ and ‘Voodoo Girls’ (2002). Thunska now also works as teacher and scholar at the film department of Bangkok University.

Other talents include Sivaroj Kongsakul with ‘Eternity’ (2010), Sompot Chidgasornpongse with his first feature production ‘Railway Sleepers’ (2014) and Santiphap Inkong-ngam. Sompot also works as a regular assistant director to Apichatpong, while Santiphap worked in his films with local groups (e.g. monks, minorities, ethnic communities).

Nontawat Numbenchapol inpressed international festival audiences with his documentaries ‘By the River’ and ‘Boundary‘ (both 2013).

Chookiat Sakveerakul rejuveniled popular Thai filmmaking for a new generation;

film editor Lee Chatametikool debuted as director in 2013 with ‘Concrete Clouds’.

Now, this brief, very subjectively compiled and hence selective list of talents already counts 19 Thai filmmakers of relevance.

More are, of course, out there — the generation of the 1980s and 1990s — and soon to be recognizable and traceable.

4. Thai New Wave Cinema:

“The possibility is not the reason.”

Tilman Baumgärtel mentions in his anthology on “Southeast Asian Independent Filmmaking” a very relevant precondition for the upcoming of this new generation of filmmakers: “The empowerment by the easy and cheap access to digital video.”

He continues to notice: “Due to digital cinema technology, they now have the opportinuity to produce their alternative and often very personal works. Interestingly, the consumption of these digital films has become something akin to a lifestyle statement among middle-class youth in all of these countries.”

What’s true in terms to digital video production is especially true for digital social network distribution in the new media world of YouTube, Vimeo, Facebook & Twitter.

One filmmaker who made extensive use of both sides of the new digital possibilities, both in production and distribution, is Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit with his works ‘36’ (2012); ‘Marry is happy, Marry is happy’ (2013) and ‘The Master’ (2014). At the moment he may be the most important figure in Thai film making to be tracked.

Interestingly enough the professional background of Nawapol is scriptwriting (and script healing). In his films he is also reflecting on media and film history as an integral part of his (digitally produced) narrative. ‘36’ was an important number in analogue 35mm photographing; ‘Marry is happy…‘ narrates a true Twitter feed based love story.

Regarding the specific contribution of narration in Thai New Wave film making for World Cinema, Zürich academic scholar Natalie Böhler contributes to Baumgärtel’s anthology with her article: “Fiction, Interrupted: Discontinuous Illusion and Regional Performance Traditions in Contemporary Thai Independent Film”. While it is true that Thai films bristle the idea of an assumed unity in narrative, time and space of the so called “Aristotelian Dramaturgy” (Brecht) in general, they do develop a very high sensitivity of local place, hence origin and occurrences in time while transcending completely the narrative plot economics of Western commercial cinematic narration. This is much more than just “regional performance traditions”.

One question however remains: Where is the “catharsis” coming from in this method of “interrupted” and “discontinuous” cinematic story telling a.k.a. narration ?

5. Thai New Wave Cinema:

“Why are we so touched by them?”

Film titles like ‘Reincarnate’ and ‘…who Can Recall His Past Lives’ paint the trace already. Thailand spiritual background in culture roots in Buddhism. Basic assumptions of Buddhism are reincarnation and karma. Present life acknowledges the existence of spirits and ghosts as living entities one has to deal with in everyday life.

If one acknowledges spirits and ghosts as living entities, they may need to have a dedicated place; a place which already is a sort of “stage” for the dealings between “me” and “them”. The strong undercurrent and relevance of visual art in public space for the uprise of Thai New Wave Cinema may have its deepest root here. More than from any other field, Thai indy cinema is highly influenced by the visual and fine arts, also originating in the general eidetic and pictographic-friendly culture of Buddhism’s spirituality.

At the same time Thailand is overflooded with prospects of money, so called “economic development” by commercialization of every aspect of everyday life. Most notable in real estate and urban development, urban shopping centers and “media channels”.

It is quite easy to understand that both concepts contradict in totality.

Beside the fact that we have learned from German playwright Heiner Müller the fact that repression of expression is always good for creating substantial art, — the antagonism of rooting in Buddhism with the contradiction of economical dynamics leading to a general unrooting delivers both substance and material for this kind of artistic creation.

Thai filmmakers have personal and touching stories to tell from growing-up under very specific biographic, local and contextual circumstances within an accelerated, rigorous and radical change in the framework of a once quiet, local, traditional and conservative society, often with dark undercurrents of political quagmire.

In brief: They have something to tell about sustaining identity under threat and from influences of the “beyond”, something which has both significance and relevance for others in a lot of other parts of the world. Unique, deep and far-reaching.

6. Going home:

Bringing international interchange to Thailand

While the prospect of rise in Thai New Wave Cinema has been bright for some 20 years now, the future is – of course – uncertain. The clouds of forthcoming turmoil for Europe and the Americas can be noticed easily; the future and days of nourishing Thailand’s independent film scene from outside the country may at one point be limited or even end completely. This may also come true for international co-productions in case of sustained and serious financial turmoil internationally.

This leads to the conclusion that Thai film making needs an understanding on how to survive on its own ressources in the long run, e.g. by creating distribution channels of their own that may also generate income in recursive funding for producing new follow-up projects.

Collective groups of filmmakers like “Mosquito Films Distribution”, “extravirgin” or “COMMETIVE” seem to have understood the underlying dynamics already. Setting up a new TV channel for high-brow indy film ware seems to be in air, somehow.

The film community in Thailand at one point also needs to deal with another new wave of younger talents: The generation of the 1980s and 1990s will soon look for funding sources regarding their initial projects, presumably in competition to already established names while searching for the same limited domestic funding ressources.

In this situation it may be considered that international exchange – which turned out to be so productive for the enrichment of the Thai indy film movement – is actually a good thing to have around, much like fresh air – and at one point this experience of international cultural exchance could or should be brought back home, to Thailand itself.

So: Where do we start from here ?

How should we start to bring together Thai and International filmmakers in Thailand ?

How can we as outsiders find out whether this intrusion might be welcomed or not ?

How could such an international interchange be improvised, orchestrated, staged, institutionalized and funded ?

Will there be an interest, support or opposition in Thai government or the cultural administration body for such an undertaking ?

How might TV journalists and TV documentary professionals in Thailand relate to efforts in professional education in filmmaking ?

We’ll need to find out.

One thought on “Film Arts in Thailand – a research”

Comments are closed.